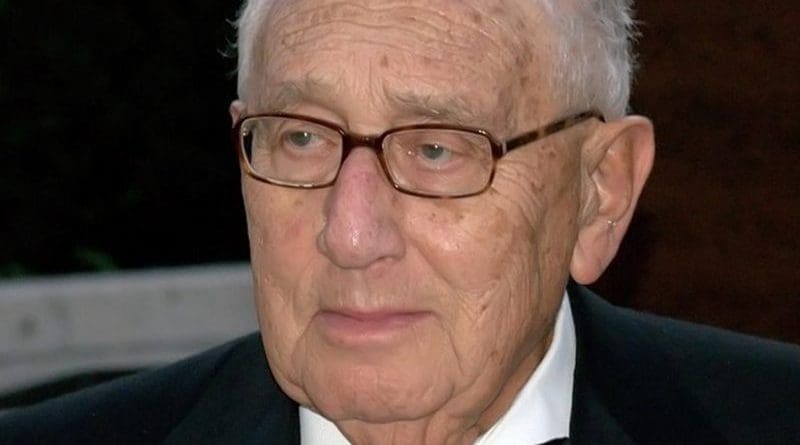

Henry Kissinger. Photo by David Shankbone, Wikipedia Commons.

The Legacy Of Henry Kissinger – OpEd

By Ambassador Kazi Anwarul Masud

Bengalis of all generations would remember with a shiver the insufferable genocide perpetrated by the Pakistani military junta on unarmed people of then East Pakistan and with gratitude to Ishaan Tharoor of Washington Post for his article titled Keeping Dhaka Ghosts Alive (24 September 2023) for reminding the present generation of the shock and disbelief that my generation had seen and suffered.

Amazingly, writes Jessica T Mathews in Foreign Affairs article (Profiles in Power-The World according to Henry Kissinger-January/February 2023) that Kissinger raised the bar still higher, and even posited that a “global war over Bangladesh” was “possible.” Few would dispute that Nixon and Kissinger were juggling critical U.S. relations with both China and the Soviet Union or that the opening of relations with China held far greater strategic value in 1971 than did autonomy for East Pakistan. But serious questions remain. Did pursuing that opening requires the stance Washington took? When policy in a democracy requires secrecy because of widespread opposition, how often does it produce a beneficial result in the long run? Do illegal acts—in this case, arms transfers—by the government lower the threshold for bad behavior, leading others, in and out of government, to break the law? Is there a better balance to be found than obtained here between a realist concern for the national interest and a decent respect for human life, including brown, non-Christian life?

Such questions raised by Jessica Mathews could be found in Henry Kissinger’s life as a realist. One could also borrow from Harvard luminary Joseph Nye Jr’s opinion, “On the negative side of his ledger is the overthrow of the Allende government in Chile; the backing of Pakistan’s massive brutality against Bangladeshis and Bengalis in the early ’70s — some people would add East Timor, where he supported the government. But the biggest of all is Vietnam and the bombing of Cambodia, which led to Pol Pot coming in with a genocidal regime. And then, the way that war ended, which is more controversial. Some people thought they ended it well. My view is that they could have ended sooner with far less loss of lives, both American and Vietnamese.”

The main context of this article though is the death of Henry Kissinger who passed away at the ripe age of 100. The British paper The Economist which had a long conversation with Henry Kissinger before his death has written that nobody alive has more experience in international affairs, first as a scholar of 19th-century diplomacy, later as America’s national security adviser and secretary of state, and for the past 46 years as a consultant and emissary to monarchs, presidents, and prime ministers.

Referring to US-China tensions, Henry Kissinger expressed his worries. “Both sides have convinced themselves that the other represents a strategic danger,” he says. “We are on the path to great-power confrontation.” Henry Kissinger added that his alarm is caused by China’s and America’s intensifying competition for technological and economic pre-eminence. Even as Russia tumbles into China’s orbit and war overshadows Europe’s eastern flank, he feared that AI was about to supercharge the Sino-American rivalry. Around the world, the balance of power and the technological basis of warfare are shifting so fast and in so many ways that countries lack any settled principle on which they can establish order. If they cannot find one, they may resort to force.

“We’re in the classic pre-World War I situation,” he said, “where neither side has much margin of political concession and in which any disturbance of the equilibrium can lead to catastrophic consequences.” The Economist in its long write up added that in his view, the fate of humanity depends on whether America and China can get along. He believed the rapid progress of AI, in particular, leaves them only five-to-ten years to find a way. Despite a reputation for being conciliatory towards the government in Beijing, he acknowledged that many Chinese thinkers believe America is on a downward slope and that, “therefore, as a result of a historic evolution, they will eventually supplant us.”

He believed that China’s leadership resents Western policymakers’ talk of a global rules-based order, when what they really mean is America’s rules and America’s order. China’s rulers are insulted by what they see as the condescending bargain offered by the West, of granting China privileges if it behaves (they surely think the privileges should be theirs by right, as a rising power). Indeed, some in China suspect that America will never treat it as an equal and that it’s foolish to imagine it might. However, Henry Kissinger also warned against misinterpreting China’s ambitions. In Washington, “They say China wants world domination…The answer is that they [in China] want to be powerful,” he said. “They’re not heading for world domination in a Hitlerian sense,” “That is not how they think or have ever thought of world order.” In Nazi Germany war was inevitable because Adolf Hitler needed it, but China is different. He had met many Chinese leaders, starting with Mao Tse Tung . He did not doubt their ideological commitment, but this has always been welded onto a keen sense of their country’s interests and capabilities.

Henry Kissinger saw the Chinese system as more Confucian than Marxist. That teaches Chinese leaders to attain the maximum strength of which their country is capable and to seek to be respected for their accomplishments. Chinese leaders want to be recognized as the international system’s final judges of their interests. “If they achieved superiority that can genuinely be used, would they drive it to the point of imposing Chinese culture?” he asks. “I don’t know. My instinct is No…[But] I believe it is in our capacity to prevent that situation from arising by a combination of diplomacy and force.” One natural American response to the challenge of China’s ambition is to probe it, as a way to identify how to sustain the equilibrium between the two powers. Another is to establish a permanent dialogue between China and America. China “is trying to play a global role. We have to assess at each point if the conceptions of a strategic role are compatible.” If they are not, then the question of force will arise.

Fareed Zakaria of the Washington Post in an article on Henry Kissinger (November 30, 2023. Henry Kissinger The Titan of Realism) quoted an obituary in the New York Times by David E. Sanger summarizing Henry Kissinger in the following words “ considered the most powerful secretary of state in the post-World War II era,” as a “scholar-turned-diplomat who engineered the United States’ opening to China, negotiated its exit from Vietnam, and used cunning, ambition and intellect to remake American power relationships with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, sometimes trampling on democratic values to do so.” On that trampling of democratic values, Gary J. Bass writes for The Atlantic that Kissinger steered the US into some of the policies for which it is most criticized globally. Bass writes: “Yet for all the praise of Kissinger’s insights into global affairs and his role in establishing relations with Communist China, his policies are better remembered for his callousness toward the most helpless people in the world. How many of his eulogists will grapple with his full record in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Bangladesh, Chile, Argentina, East Timor, Cyprus, and elsewhere?”

Harvard luminary Joseph Nye Jr. (Judging Henry Kissinger. Did the Ends Justify the Means? By Joseph S. Nye, Jr. November 30, 2023) he justified the genocide in Bangladesh by quoting his own words In the war of secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan, Kissinger and Nixon were criticized for not condemning Pakistani President Yahya Khan for his repression and bloodshed in Bangladesh, which resulted in the deaths of at least 300,000 Bengalis and sent a flood of refugees into India. Kissinger argued that his silence was needed to secure Yahya’s help in establishing ties with China. But he has admitted that Nixon’s dislike of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, which Kissinger abetted, was also a factor Unquote. Equally Joseph Nye Jr. asks how does Kissinger measures up on these criteria of moralism versus realism. In Joseph Nye’s words quote He certainly had great successes: the opening of China, establishing détente with the Soviet Union, and managing crises in the Middle East, all of which made the world safer.

In China, for instance, Kissinger and Nixon had the vision and temerity to guide world politics away from Cold War bipolarity and reintegrate Beijing into the international system. They had to ignore the ugly nature of Mao Zedong’s totalitarian regime. Similarly, in managing détente and arms control with Moscow, Kissinger had to accept the legitimacy of another totalitarian regime and go slower than many Americans wanted in pushing the Kremlin to allow Jewish emigration. Nonetheless, his position helped lower the risk of nuclear war and create the conditions in which the Soviet Union itself gradually eroded. Here, again, the moral gains far outweighed the costs. And although he took risks by raising the alert level of U.S. nuclear forces to DEFCON 3 during the Yom Kippur War in the Middle East, Kissinger’s judgment turned out to be right. Ultimately, he managed to reduce tensions Unquote. In short, it is too early to pass judgment on the success and failure of a person like Henry Kissinger. The present article is only a drop in the ocean of books, articles, and research papers to come in the future unveiling the complex character of Henry Kissinger who lived a life that very few individuals can aspire to live.

No comments:

Post a Comment