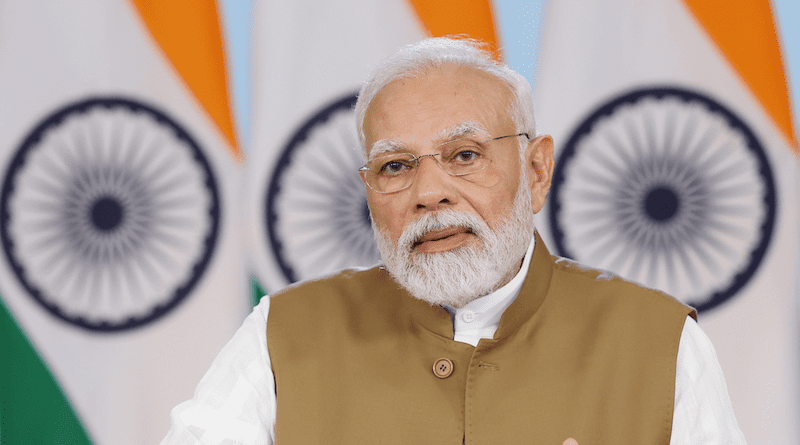

India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo Credit: India PM Office

India: Can Narendra Modi Repeat His Past Election Victories This Time Too? – OpEd

By Ambassador Kazi Anwarul Masud

India is poised to become populous nation in 2023, with an estimated population of 1.428 billion people (17.8% of the global population). By the end of April 2023 India’s population is expected to be 1,425,775,850 slightly higher than China’s population of 1.4 billion in 2022. UNFPA estimates India’s population at 1.4286 billion by mid-2023 surpassing China’s population. India’s population growth is driven by fertility levels, and together, China and India account for more than one-third of the world’s total population.

It’s important to note that these figures are estimates, and population dynamics can change over time due to various factors such as birth rates, mortality rates, and migration patterns. The crossover between India and China reminds us of the importance of long-term planning and addressing the needs of different age groups. As India continues to grow, ensuring the well-being and development of its population remains a critical priority. This sub-continent is holding its election, projected by the famous British newspaper The Guardian, as a certain victory for current Prime Minister Narendra Modi despite world wide condemnation of his regime for the persecution of the minority Muslim community, in particular by the Muslim majority areas of the world. In a write up Michael Kugelmen in South Asia Brief in Foreign Affairs reported on the most recent events relating to elections in India.

India’s national election begins on 19th April and runs for six weeks, through June 1. At first glance, the vote may seem similar to two others in South Asia this year. Just as in Bangladesh in January and Pakistan in February, an incumbent government is favored to win, and the election is playing out against a backdrop of sidelined opposition leaders and growing crackdowns on dissent.

However, India’s election and its broader political environment stand in contrast to political trends across the region—mainly because of the striking popularity and longevity of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). A recent survey put Modi’s public approval rating at 75 percent, a remarkably high figure for a head of government in office for nearly a decade. Many factors account for this popularity: Modi’s personality, his leadership model, his achievements, his ideology, and India’s weak political opposition. The main electoral uncertainty is not if Modi and the BJP will win, it’s by how much. Many of Modi’s critics say that India’s electoral playing field is unequal, but that isn’t quite accurate. They point out that India’s government has arrested opposition leaders on politically motivated charges and increased its influence over the country’s election commission, damaging opponents’ prospects.

But the BJP enjoys overwhelming support, and the national political opposition does not. Even if the Indian state weren’t targeting opposition parties, such is the strength of the BJP that the opposition’s chances of electoral success might not improve that much. Away from national politics, the calculus is a bit different. The BJP has lost a few recent state and local elections to either the main opposition Indian National Congress or smaller regional parties. But these parties can’t hold a candle to the BJP’s countrywide clout. Then there is the longevity factor. In South Asia, few elected leaders or parties have held power as long as Modi and the BJP. Nepal has had 13 governments since 2008. Pakistan has seen a series of weak coalition governments since the end of its formal military rule the same year. Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe took office in 2022, after his predecessor resigned amid anti-government protests. Only Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, has held office longer than Modi—since 2009—and she has benefited from polls that election observers have deemed not free or fair.

Both Modi’s popularity and the fact that India’s opposition hasn’t been able to put forward a strong, charismatic leader that can counter him suggest that the prime minister will face little threat to his political survival as long as he stays in office. Some reckoning for the BJP may not be that far off, even assuming the party wins this year. Whether Modi opts to try for a fourth term in 2029 remains uncertain. If not, the BJP will face major questions, chief among them the issue of his successor. The appeal of Hindu nationalism would help the BJP’s cause, but it would need to make headway on long-standing issues that could make it vulnerable, from widespread unemployment to the challenge posed by China. For now, Modi occupies a special status as one of South Asia’s most popular and longest-tenured leaders, with little intrigue attached to an election that is likely to bring him another huge public mandate. It’s a far cry from the volatility that has characterized polls and politics elsewhere in the region in recent years.

Rohan Mukherjee of London Assistant Professor of London School of Economics and Political Science in his article title A Hindu Nationalist Foreign Policy wrote that under Narendra Modi India Is Becoming More Assertive (dated April 4, 2024) and that he is not the first Indian leader with global ambitions. The country’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, also sought a leading role for India and worked energetically from the 1940s to the 1960s to promote a distinct brand of foreign policy—nonalignment with both the Soviet Union and the United States—through international institutions. But while Pandit Nehru’s efforts resonated with only a narrow domestic elite; the wider populace was too beset by poverty to care about intangibles such as international recognition. India today, by contrast, is a rising power whose population is primed for leaders to manipulate national aspirations for domestic and international gains. Narendra Modi has also successfully used a more confident and assertive society and diaspora to bolster his party’s political fortunes and to improve India’s global standing.

It is, in some respects, surprising that Narendra Modi could capitalize so effectively on foreign issues. The prime minister had minimal diplomatic experience when he took office, in 2014. Yet this lack of familiarity enabled him to craft a new way of interacting with the world, one that turned diplomacy into performance art for the masses. As a populist leader accustomed to bypassing traditional institutions, appealing directly to his supporters, and tightly controlling information, Narendra Modi (and his government) used the media and large rallies to great effect. The party is constantly reaching out to people everywhere, trying to gain supporters. Even with the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, Narendra Modi has undertaken more international visits in his two terms as prime minister than his predecessor, Manmohan Singh, did in his two.

The growing importance of India cannot, of course, be credited entirely to Modi or his government’s initiatives (or those of past prime ministers). The country has been helped, albeit indirectly, by China. As Beijing has become a persistent threat to its neighbors in Asia and to the West, India’s stock has risen. The United States, in particular, is wooing India in an effort to constrain China’s ambitions. As long as New Delhi can help countries compete with Beijing, India will have plenty of international partners, giving it considerable room for maneuver in its external relations. But China’s story is also a cautionary tale. As Beijing arrived as a world player, it abandoned its strategy of building friendly ties with other countries based on mutual economic gain. Instead, driven by popular and elite nationalism, it began strongly asserting claims to contested territory, acting recklessly in its own region, and demanding deference from others—alienating its neighbors and virtually every major power except Russia. This path is particularly fraught because rising nationalism exacerbates routine conflicts of interest. A society and polity that take offense at even minor slights will quickly encounter pushback from other states, in turn intensifying domestic anxieties and feelings of wounded pride, leading to a vicious cycle of provocation. U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit to Taiwan provides a case in point. Beijing described the visit as a provocation and warned the United States not to “play with fire.” Pelosi, unbowed, went anyway. China then began conducting military exercises around Taiwan, further raising the stakes in the strait. Ironically, when the dust settled, Chinese nationalists accused their government of making empty threats and not doing enough to stand up to the United States. India is still early in its trajectory as a rising power. But there are signs it may fall into a similar trap.

According to U.S. intelligence officials, New Delhi assassinated a Sikh Canadian national—officially designated a terrorist by the Indian government—on Canadian soil in 2023. Ottawa condemned the attack and demanded an explanation from New Delhi. Instead of seeking a way to defuse this crisis, it took umbrage at Canada for harboring Sikh separatists and pledged to protect India’s security (while also denying the allegations). New Delhi also moved to expel Canadian diplomats and suspend new visas for Canadians wishing to visit India. Later in the year, U.S. officials accused New Delhi of plotting to assassinate a Sikh American, sparking another dispute. When foreign policy itself becomes nationalist, it gives rise to self-defeating risks. These episodes command worldwide attention. India has come to realize that rise of China and eternal enmity of Pakistan gives little scope to India but to strengthen relations with the US.

Conclusion

As a rising power, India is still far from that level of global game of pull and increasing the countries’ influence in global affairs. A nationalist diplomacy backed by an increasingly confident and assertive public will also make such issues difficult to resolve by limiting the scope for compromise. Voters, for example, may turn against a government that—having set high expectations—falters in protecting expansive versions of the country’s interests and honor. National pride may know no bounds, but foreign policy must operate in a highly constrained environment. India’s political leadership will therefore have to work carefully to ensure that its nationalist diplomacy does not undermine national objectives. It may be relevant here to mention Indian Foreign Minister Dr Jaya Shankar’s reference to Goldilocks’ Principle relating to Western attitude of keeping India limited within bounds so that India’s proclivity to curve an independent course of its own may not affect Western policies. In any case India’s friends and partners will have to adjust to India’s assertive demeanor—in part, by making room for the country as it ascends in the international order.

No comments:

Post a Comment