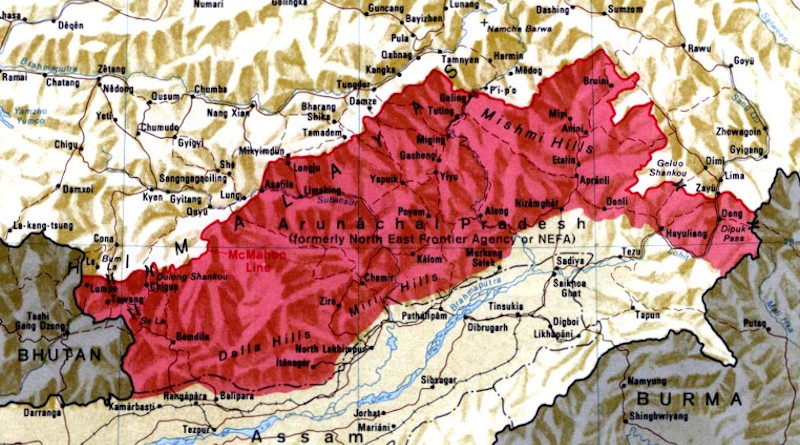

The McMahon Line forms the northern boundary of Arunachal Pradesh (shown in red) in the eastern Himalayas administered by India but claimed by China. Credit: CIA, Wikipedia Commons

India’s Perilous Border Standoff With China – OpEd

By Ambassador Kazi Anwarul Masud

Mayuri Banerjee a Research Analyst with the East Asia Centre at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi. Her research focus is on India-China relations. She primarily looks at the role of memory and trust in India-China relations after the 1962 war and Indian media’s perception of China. In an article she traced the history of the Sino-Indian border dispute has a long and complex history. If one were to look for some key points one could mention: Aksai Chin: One of the disputed territories is Aksai Chin, which is administered by China but claimed by India. It lies at the intersection of Kashmir, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Aksai Chin is mostly uninhabited high-altitude wasteland, but it has significant pasture lands at the margins.

Disputed territory is south of the McMahon Line, in an area formerly known as the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh). The McMahon Line was signed between British India and Tibet as part of the 1914 Simla Convention, but China disowns this agreement, stating that Tibet was not independent when it signed the Simla Convention.1962 Sino-Indian War: The conflict escalated in 1962 when Chinese troops attacked Indian border posts in Ladakh in the west and crossed the McMahon Line in the east. The war resulted in significant casualties. There were border clashes in 1967 in the region of Sikkim, despite an agreed border. In 1987 and 2013, potential conflicts over the Line of Actual Control (LAC) were successfully de-escalated.

Multiple skirmishes broke out in 2020, leading to dozens of deaths in June. Agreements signed in 1993 and 1996 aimed to address the boundary question, including confidence-building measures and defining the LAC. Various dispute resolutions have been established over the years. In summary, the India-China border dispute remains ongoing, with historical roots and periodic tensions. Diplomatic efforts continue to find a resolution to this complex issue. Assessing the success of Border Dispute Management Talks and Confidence-Building Measures.

The success of the bilateral dialogue mechanisms and confidence-building measures described above needs to be assessed according to three aspects; management of border conflict, addressing the bilateral trust deficit, and resolution of the border dispute. A cursory review of the state of affairs indicates that, in all three aspects, both countries have achieved minimal success. For instance, in the matter of border conflict management, the maintenance of peace and tranquility along the LAC has been one of the most important stated objectives. Although China and India have been able to avert a major 1962-style confrontation, the number of military incursions by China has risen sharply, from 334 in 2014 to 606 in 2019. Also, military standoffs between the two countries have grown longer and more difficult to resolve. Simultaneously, local feuds between the armies have inclined toward more violence, that is from fist fights and throwing stones, the armies of the two sides have resorted to more violent measures including the use of clubs studded with nails or wrapped with metal barbed wire. These instances point toward a lack of local-level communication and understanding, which persists amid the backdrop of diplomatic proclamations of friendship and cooperation. Likewise, despite high level political and diplomatic exchanges and frequent meetings of the top leadership, the trust deficit between the two countries has only widened.

There exists the perception of a considerable security threat on both sides as India and China have moved rapidly to upgrade their border infrastructure and military capabilities along the disputed border on the sidelines of the Special Representative Talks and Joint Working Group meetings. In recent years, a vigorous border infrastructure race has developed between the two countries, wherein both sides have engaged in building extensive road and railway connections on their respective sides of the border, upgrading military facilities, and increasing overall troop deployments for quick mobilization. This in turn has aggravated insecurities in both countries and is considered one of the primary reasons for the frequent border skirmishes along the LAC. In particular, the Doklam (2017) and Galwan Valley (2020) clashes were triggered by road-building activities undertaken by China and India, respectively. In view of increasing military capabilities, assertive behavior and intense distrust, the notion of peace along the LAC seems dependent on the political wisdom of their respective governments. Even after fifteen rounds of Joint Working Group meetings and eighteen rounds of Special Representative Dialogues, the border dispute is far from being resolved. Even though the negotiation process follows a generous principle of package settlement through a sectoral approach, the two countries have failed to go beyond routine delegation meetings and joint declarations.

The ascent to power of Xi Jinping in China and Narendra Modi in India, known for their strong leadership and corporate style of politics, had raised hopes for a final settlement of the border dispute, but domestic political considerations and strategic threat perceptions continue to severely constrain the ability of these political leaders to undertake sweeping decisions to resolve the dispute. The border dispute undeniably remains one of the major issues impinging on Sino-Indian bilateral ties.

Experts contend that the primary reason for this difference in approaches is that the disputed border does not pose a security threat to China, and therefore Beijing is willing to wait for a more beneficial resolution. In contrast, New Delhi sees the border dispute as source of instability and worries and that China would use the unresolved border to bully India. The third factor inhibiting the resolution of the border dispute is intense nationalism in both countries.

For China, the border dispute is intrinsically linked to Tibet and the Dalai Lama, and since the CCP has always projected the Tibetan government-in-exile in a negative light, territorial concessions involving Tawang will not only endanger China’s own rule in Tibet but will also be seen domestically as sign of weakness; a terrifying prospect for the Chinese leadership. As for India, no political party would be able to propose a territorial exchange with China without seriously jeopardizing its electoral prospects, as the memories of 1962 war continue to haunt the Indian national psyche.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and China’s growing influence in South Asia have emerged as new irritants for Indian policy makers. Similarly, Beijing too is annoyed by India’s increasing proximity with Southeast Asian countries and its diplomatic-military exchanges with the United States, Japan, and Australia. These issues further erode political will in both countries and in this context territorial exchange by swap or political settlement appears a daunting task. As evinced by the recent Galwan Valley clashes, managing the border dispute is both a political and an economic exigency for India and China because any major confrontation between the two countries will not only hurt the long-term prospects for development of both, but will also have significant repercussions on Asian stability and prosperity.

The two countries should also aim toward building strategic trust through open dialogue, exchange of information, and verification mechanisms along the disputed border. Enhancing military-to-military communication, technological collaboration and engagement on multilateral platforms remain indispensable toward building trust. Public perception is another key area that needs to be urgently addressed through civilian exchanges. This would go a long way toward dispelling stereotypes and negative perceptions. Track-II dialogue involving strategic-affairs experts and academics from the two countries could also be organized to identify new areas for cooperation. For the foreseeable future, the border dispute will remain a pressing challenge in Sino-Indian ties, however, it is in the national interest of both countries to prioritize their larger bilateral relationship, while at the same time erecting confidence-building measures and dialogue mechanisms to better preserve the benefits accruing from the relationship. The border dispute undeniably remains one of the major issues impinging on Sino-Indian bilateral ties.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and China’s growing influence in South Asia have emerged as new irritants for Indian policy makers. Similarly, Beijing too is annoyed by India’s increasing proximity with Southeast Asian countries and its diplomatic-military exchanges with the United States, Japan, and Australia. These issues further erode political will in both countries and in this context territorial exchange by swap or political settlement appears a daunting task. As evinced by the recent Galwan Valley clashes, managing the border dispute is both a political and an economic exigency for India and China because any major confrontation between the two countries will not only hurt the long-term prospects for development of both, but will also have significant repercussions on Asian stability and prosperity. Track II dialogue involving strategic-affairs experts and academics from the two countries could also be organized to identify new areas for cooperation. For the foreseeable future, the border dispute will remain a pressing challenge in Sino-Indian ties, however, it is in the national interest of both countries to prioritize their larger bilateral relationship, while at the same time erecting confidence-building measures and dialogue mechanisms to better preserve the benefits accruing from the relationship.

The famous Diplomat in a report on the US containment of the Sino-Indian relations has reported that The United States and India have just completed a ministerial dialogue between the U.S. secretaries of state and defense, Antony Blinken and Lloyd Austin, and their Indian counterparts, Minister of External Affairs Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Rajnath Singh. This “2+2 Dialogue” was preceded by a video conference between U.S. President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and both leaders said they looked forward to meeting again shortly in Tokyo.

Although the “2+2” was nominally focused on international security and was the first to occur since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the world’s two largest democracies paid relatively little attention to the largest international assault on democratic values since World War II and what Russia’s assault means for international peace and security.

Jaishankar’s views are of tremendous importance to the Modi government and to Modi himself. Not only has Jaishankar been the minister of external affairs since the start of Modi’s second term, but he became foreign secretary soon after Modi began his first term as prime minister, an office to which Modi arose without extensive experience in international security matters. A thumbnail and easily accessible statement of Jaishankar’s international framework can be found in his talk to the Atlantic Council. This framework is important not only because of the office held by Jaishankar, but also because it is largely a distillation of the views of many Indians, particularly those of India’s traditional academic and governmental elites.

One must not forget that Jaishankar’s concept of “the West” is now centered on the United States. This concept evidently derives from U.S. leadership of a network of treaty obligations that were designed to constrain the Soviet Union and international communism. At one point in his talk, Jaishankar references Japan and South Korea, and even all the OECD countries, as part of “the West.” In this analysis, “the West” has become not a geographic designation but a political concept apparently growing out of the Cold War. Again, India is not a part of “the West.” Adding to the historic estrangement caused by colonialism, the U.S., as the leader of “the West,” has imposed on India a “Goldilocks” policy of both supporting India and suppressing India. According to Jaishankar, this is to ensure that India is neither too weak nor too strong but, like the porridge in the Goldilocks story, somewhere in between. Prime historical examples of this, according to Jaishankar, are the 1962 invasion by China, where the U.S. supported India, and the 1971 war for the independence of Bangladesh where the U.S. was not supportive. This historical interpretation of East vs. West fits snugly with the other major dichotomy of the Jaishankar doctrine, namely the political vs. non-political aspects of the East-West relationship.

A strength of the Jaishankar doctrine is that it allows for a full range of cooperation on “non-political” aspects of the U.S.-India relationship. There is a recognition that the United States has had a policy of strengthening India from an economic developmental perspective and has been a fount of growth for world development generally. Now that India has largely dismantled its top-down economic model, or “license raj,” the way is open for full cooperation on all “non-political” fronts. However, when it comes to “political” endeavors, i.e. those having to do with international security and strategic matters, the aforementioned East vs. West analytic dichotomy requires that the relationship must be more circumscribed. The Cold War ended badly for India in the sense that the USSR and Russia were no longer the strong sources of support they had been up until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Still the political nature of the India-Russia relationship seems to require that India maintain a distance from the United States and the West where Russia is involved. This distancing is often referred to by Indian commentators as “strategic autonomy.” A key component of this strategic autonomy seems to be resistance to outside requests, comments, or even questions concerning India’s strategic or political choices. Apparently still influenced by what Jaishankar formulates as the two hundred years of national humiliation by the West, such entreaties may be viewed as infringements on strategic autonomy if not national sovereignty. This was on display in Jaishankar’s response to the press at the end of the 2+2 meeting.

But a full U.S.-India partnership requires that India adjust the analytic approach which contributes to India standing aside when it comes to opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The old “East vs. West” dichotomy no longer applies to U.S.-India relations, if it ever did. Certainly, India and the U.S. are different, but these two great democracies have far more in common than India has with the traditional pillars of “the East” – Russia and China.

This is particularly true when it comes to the fundamental value and rule of the post-World War II era: that nations must refrain from the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. Some may seek to justify the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the basis of U.S. transgressions of the past. The rule of law requires that each situation be judged on its own merits. In the case of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the use of force is singular in its breach of the rules that have kept the planet from another world war over the past seventy years. The dichotomy between political and non-political interests is also in need of adjustment. India is no longer a new republic struggling to throw off the remnants of British colonialism and rightly sensitive to perceived restraints on its sovereignty. India is a great power. The U.S. needs to treat India like a great power, and India needs to act like one.

No comments:

Post a Comment